On Tuesday, the Government will publish an audit of race disparity across public service outcomes. The data, which will be publicly available, outlines race-based inequality in health, education and employment services, and within the criminal justice system. This is a very welcome development: previous Resolution Foundation research found that such disparities are very real when it comes to differences in living standards. In order to tackle them we need a better understanding of where and how they exist – before of course turning to the really important bit: action to actually do something about them.

Ongoing Resolution Foundation research analysing the link between education, employment and pay gives us reason to be positive about one of these issues: there have been very substantial rises over the past two decades in the proportion of people from Black and Minority Ethnic groups that have a degree. Unfortunately, however, rising educational attainment has not directly translated into an end to big disparities in employment outcomes: on average, graduates from Black and Minority Ethnic groups have lower employment rates and when in work are more likely to be in lower paid occupations than their white counterparts. They are also, on average, paid less despite working in similar types of occupations. Understanding the patterns of, and the drivers behind these inequalities is critical if they are to be reduced over time. That is why we should applaud the government for bringing such important data sources to the fore.

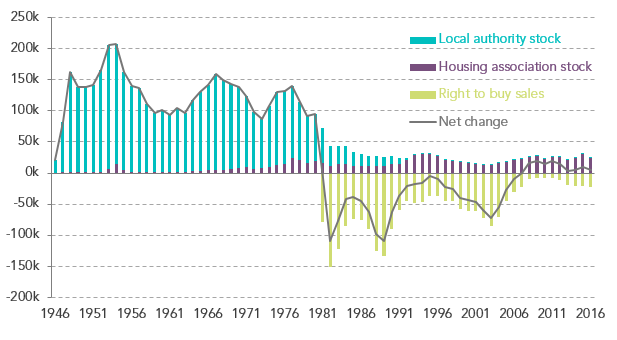

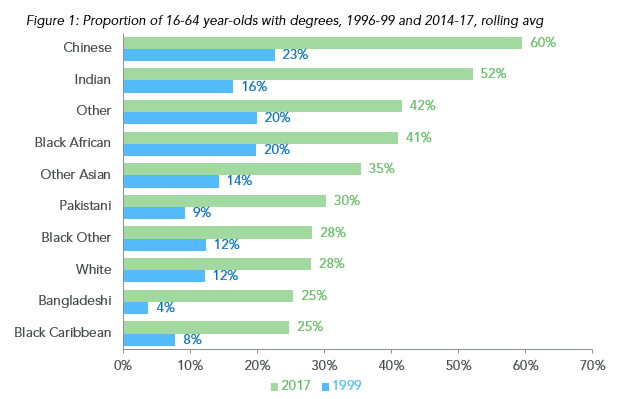

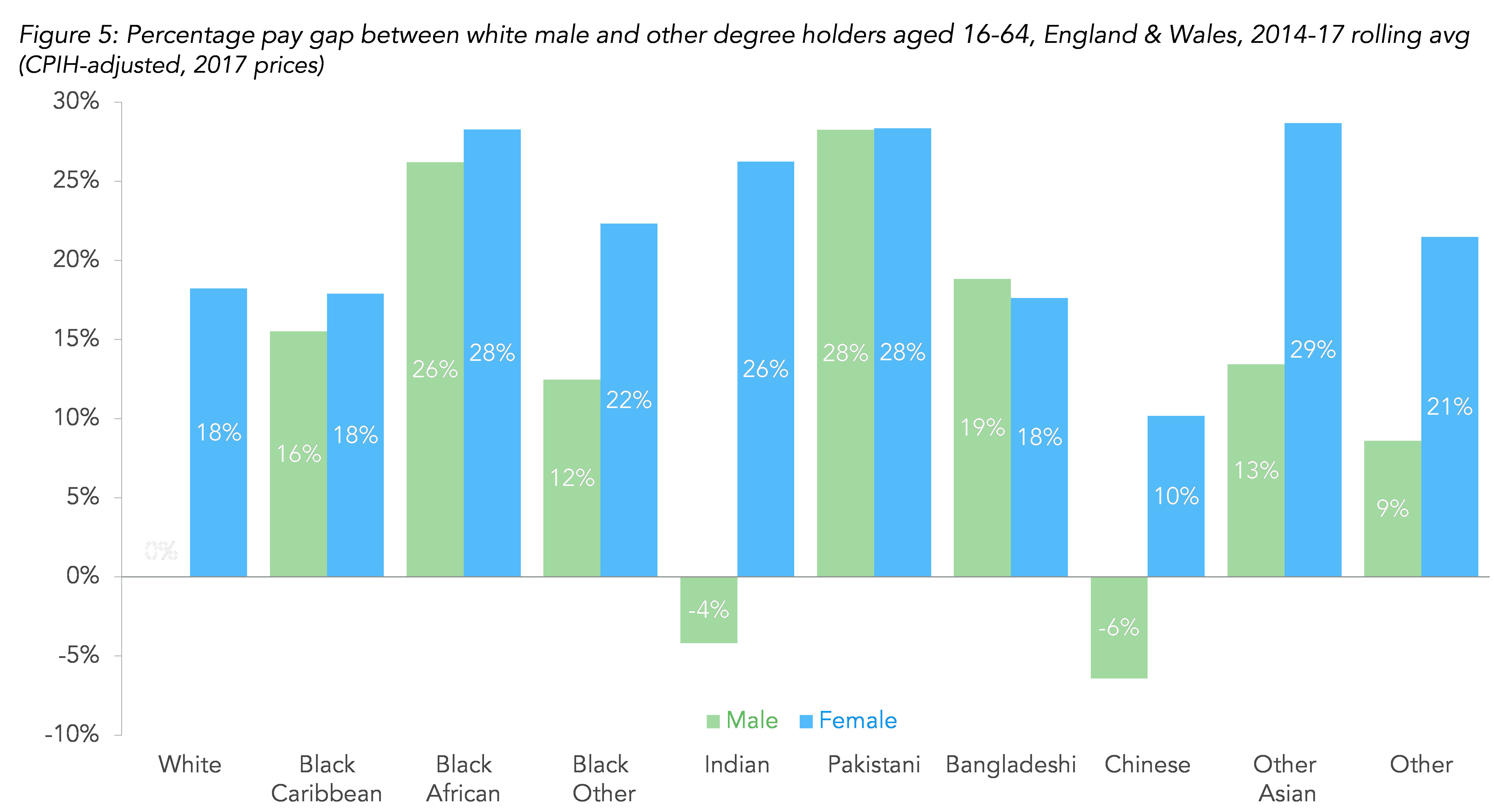

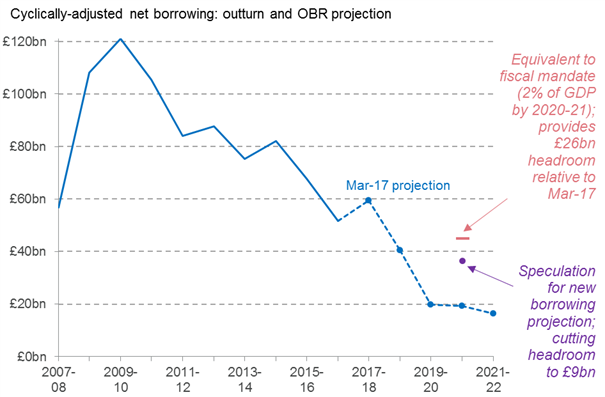

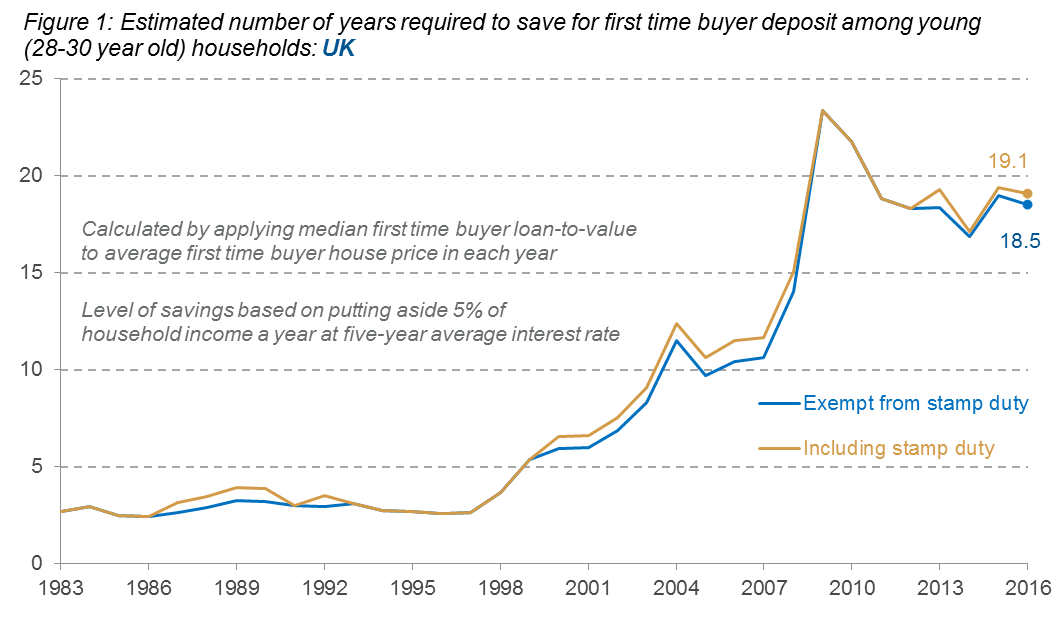

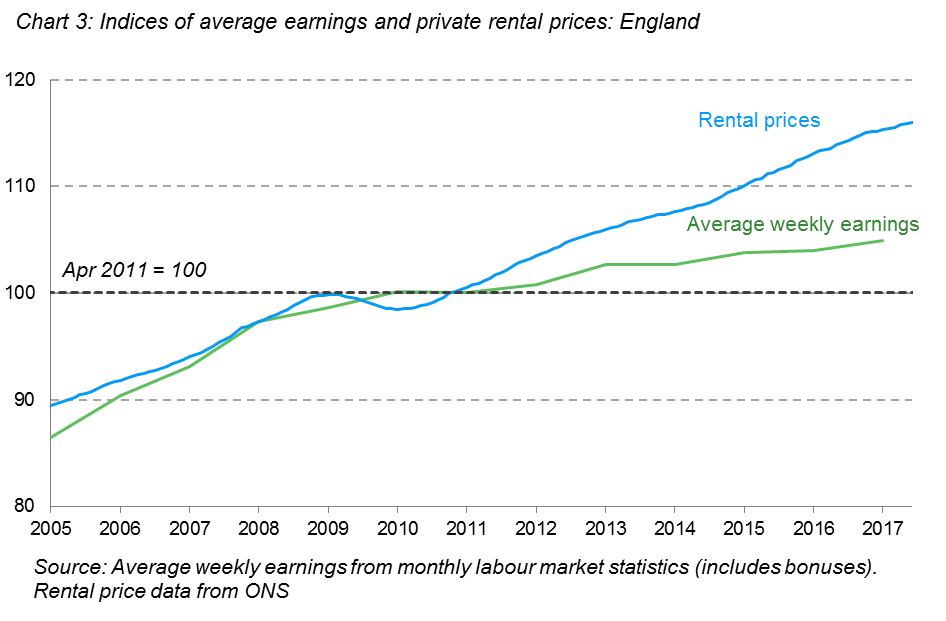

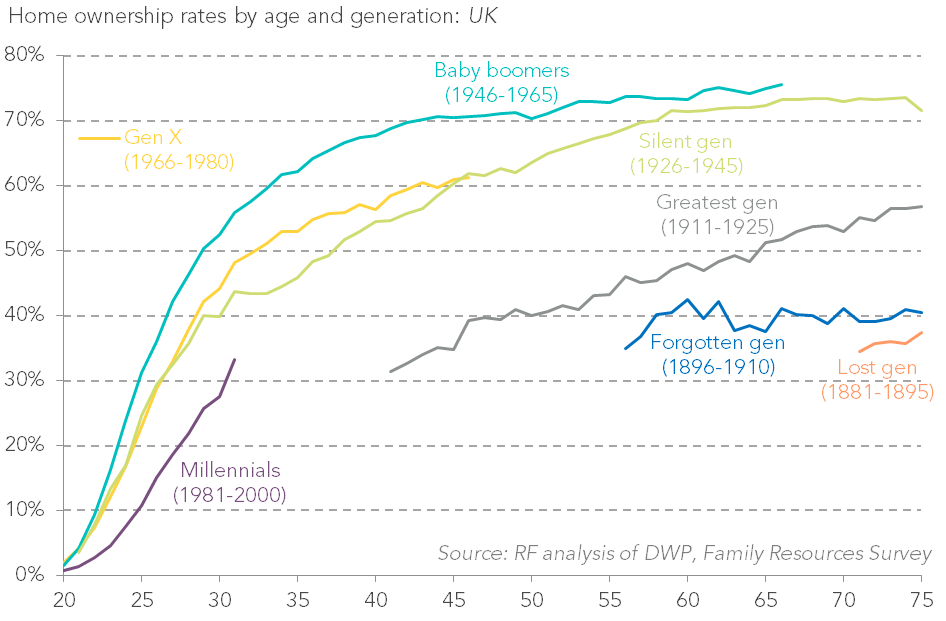

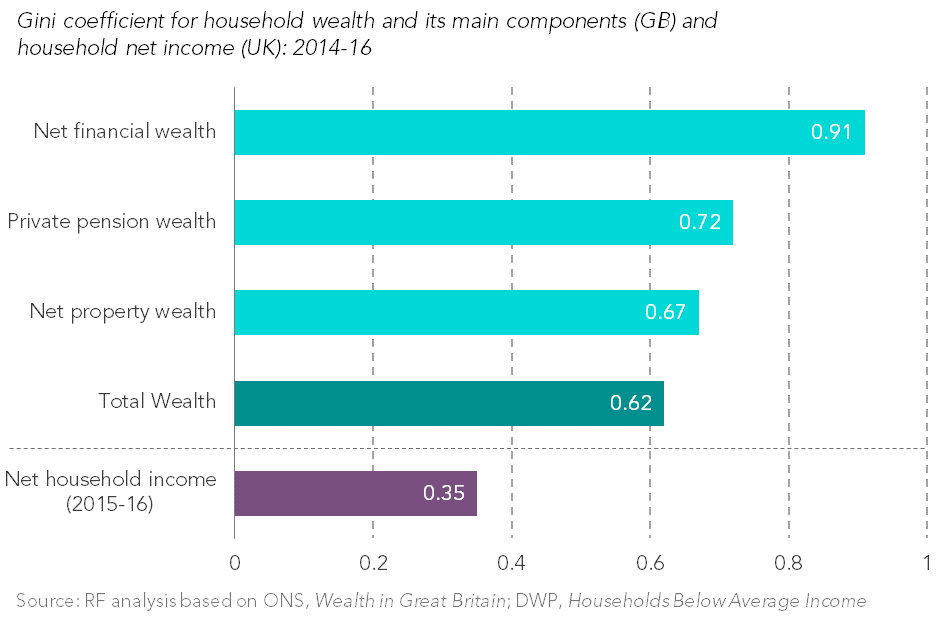

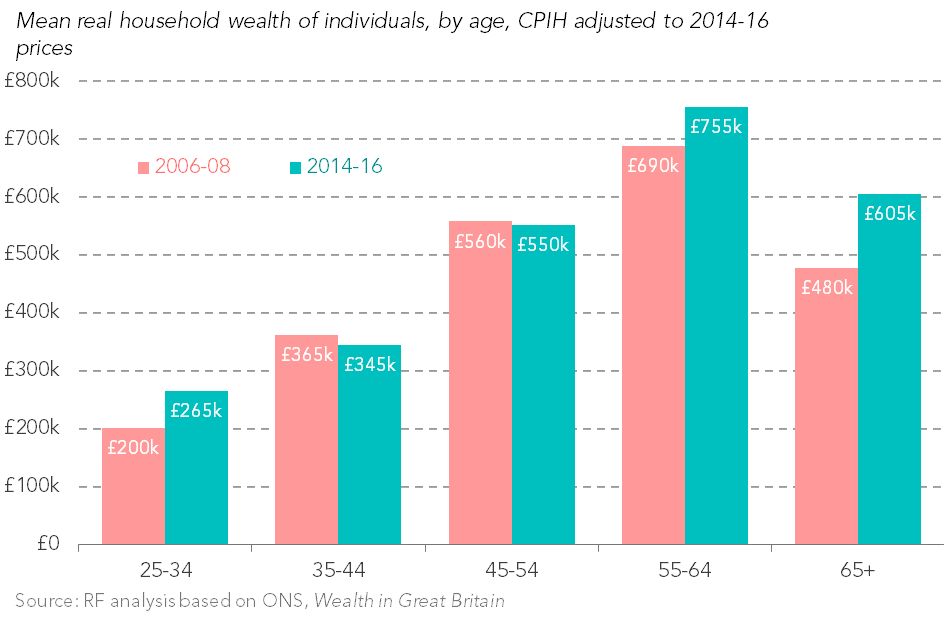

According to the Office for National Statistics’ Labour Force Survey, between 1996 and 2017, the proportion of working age (16-64) people in the UK with degrees (or higher) has more than doubled, from 12 to 30 per cent. Rates of attainment growth vary across different parts of the UK population and this variation is significant when viewed through the lens of ethnicity. As Figure 1 illustrates, the proportion of working age people that hold a degree – by ethnicity – varies from 25% (Black Caribbean) to 60% (Chinese).

![]()

Source: Labour Force Survey. Figures for 1996-99 are UK-wide, figures for 2014-17 refer to England and Wales only. Currently enrolled students are excluded.

Even groups that currently have a lower than average proportion of graduates have experienced considerable growth over the past two decades: for example, the proportion of working age graduates with a Bangladeshi background grew by (almost) a multiple of six in twenty years alone. The proportion of graduates with a Pakistani background more than trebled in the same time frame. Some of this is indeed driven by younger birth cohorts, and the age profile of some ethnic groups but while those under the age of 35 do, across all ethnicities, have higher rates of degree attainment, the rough ordering displayed above remains.

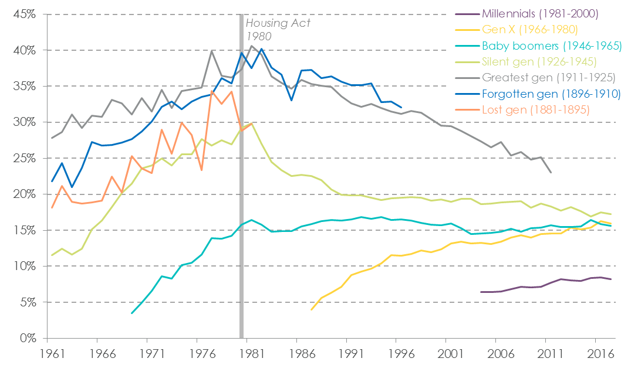

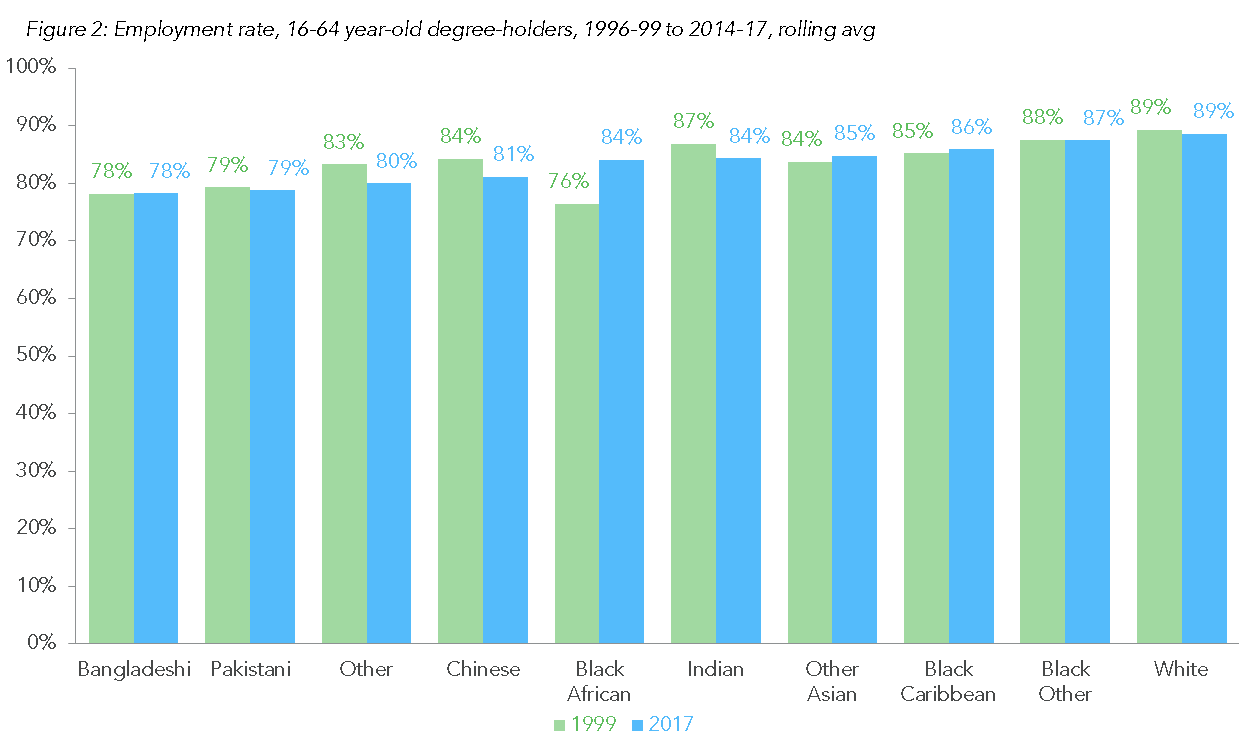

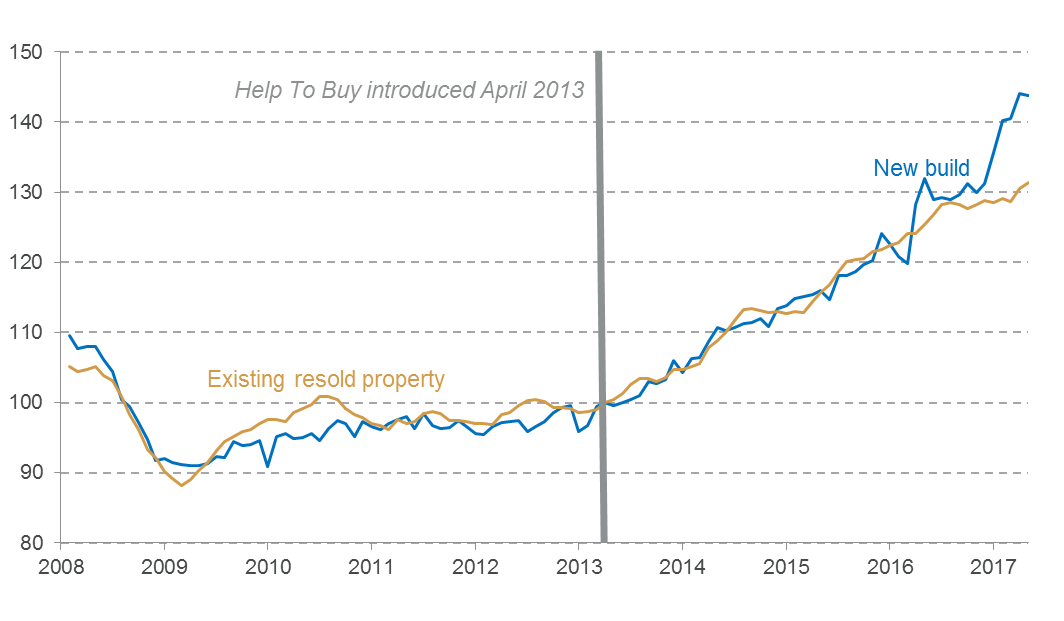

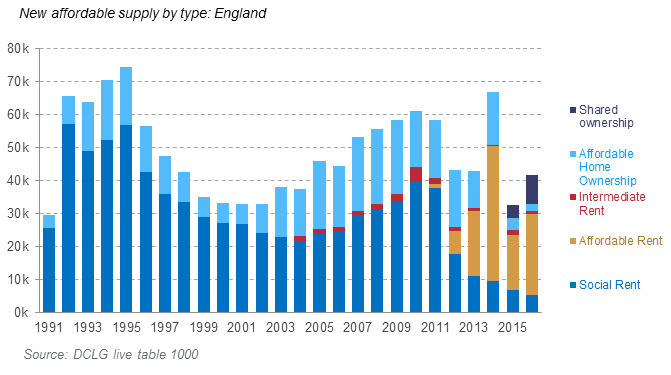

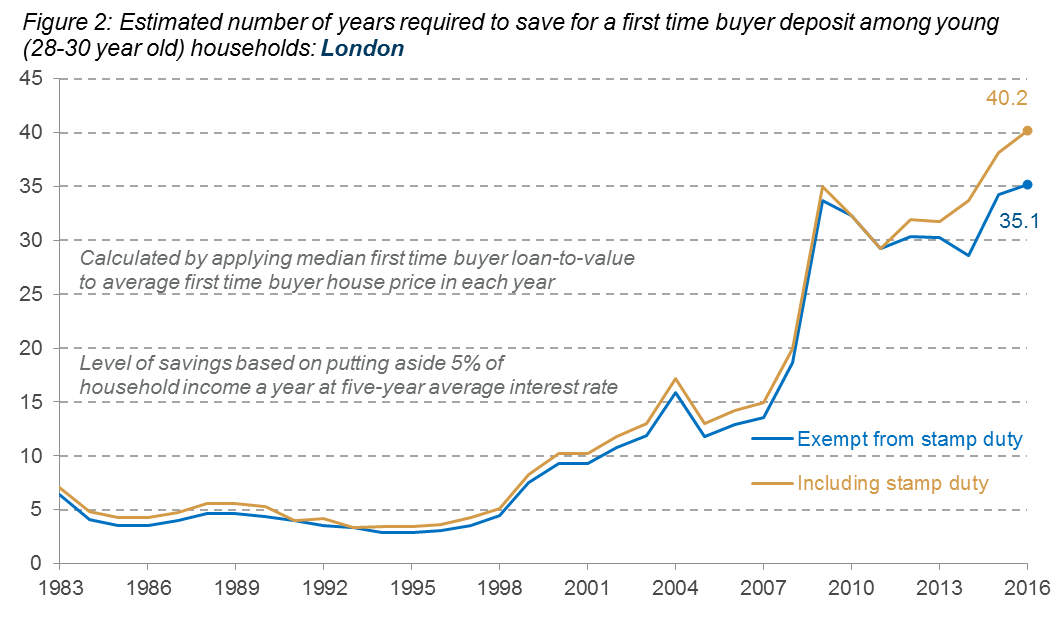

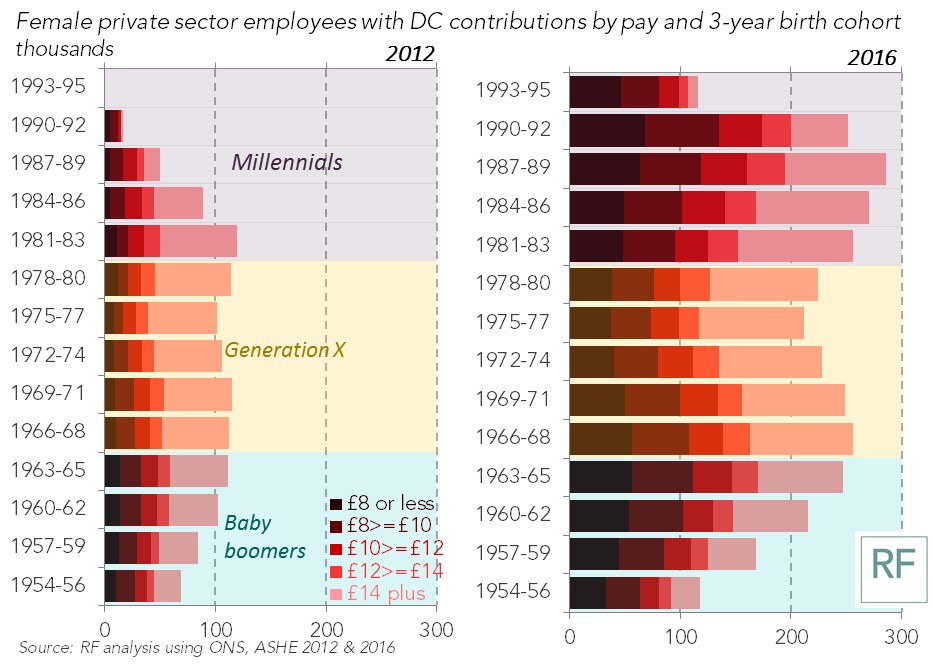

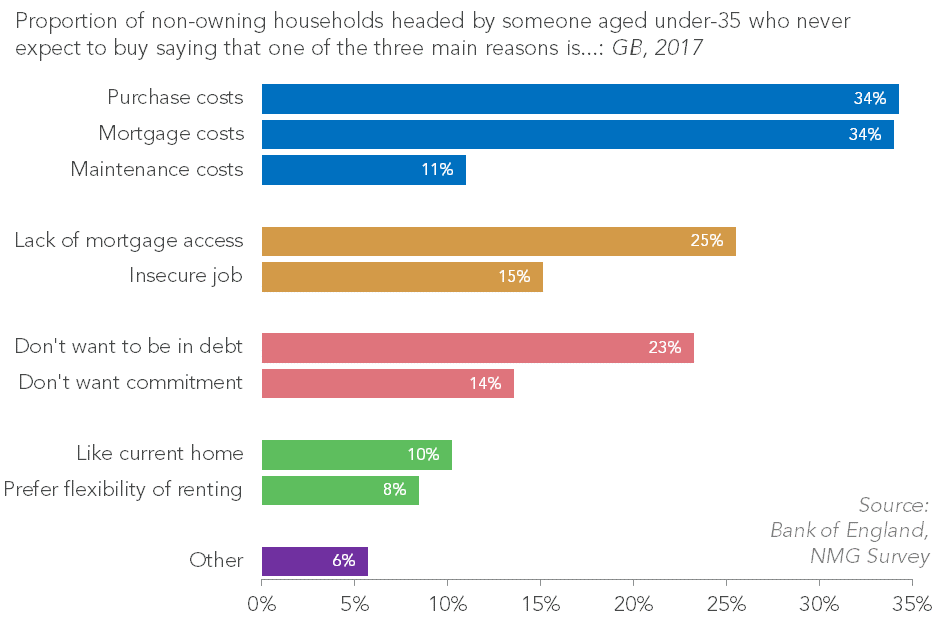

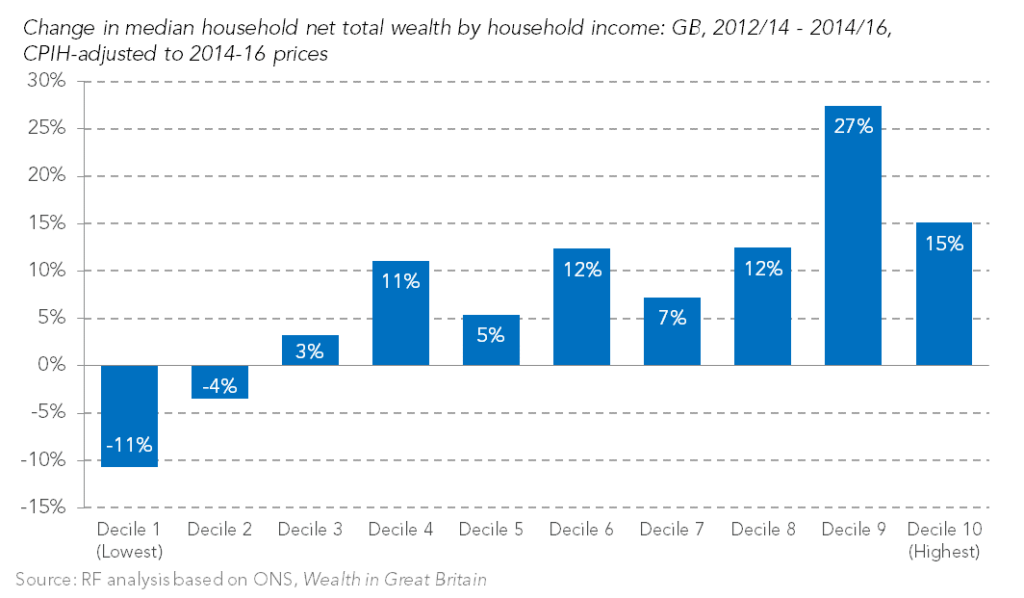

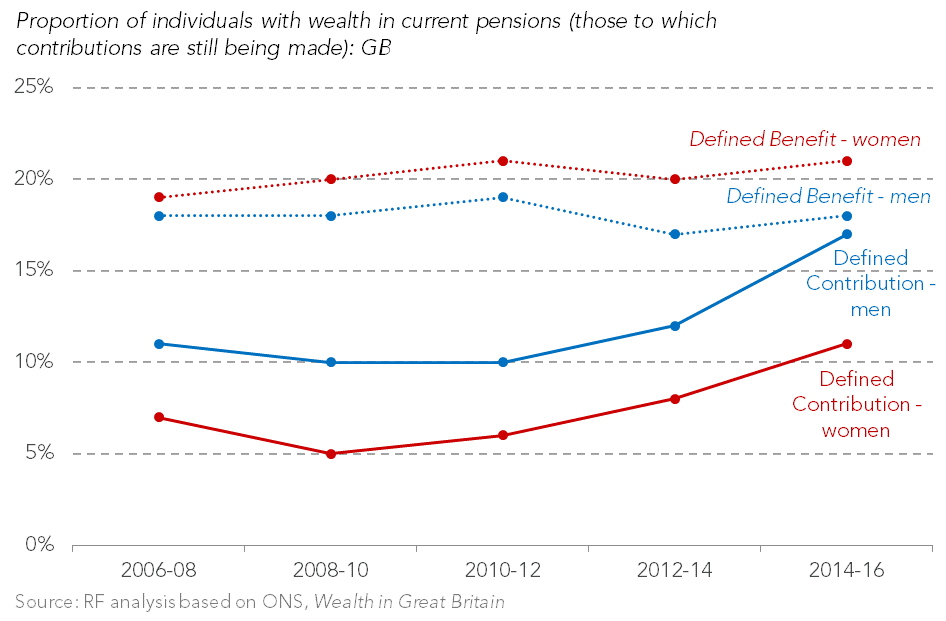

Having a degree, on average, continues to lead to higher pay and better prospects for career progression than not having one. And yet, despite rapid – and substantial – levels of degree attainment, once many Black and Minority Ethnic graduates leave university and enter into the labour market, they have a very different experience from their white counterparts. As illustrated in Figure 2, the employment rate for working age graduates ranges from 78% (Bangladeshi) to 89% (white). With some exceptions (a rise for Black African graduates), these rates have held largely stable over the past two decades.

![]()

Source: Labour Force Survey. Figures for 1996-99 are UK-wide, figures for 2014-17 refer to England and Wales only. Currently enrolled students are excluded.

The picture is slightly different when we isolate those under the age of 35: here the gap in employment rates between white and other graduates is larger. For example, the gap between white and Bangladeshi graduates age 16-64 is 10 percentage points; for those age 16-34 (students excluded) is 15 percentage points. In addition, the above chart does not account for birth cohorts, gender or region, which will likely impact employment and pay figures for different ethnic groups, depending on the extent of regional concentration for each group. All of these factors will be analysed in further detail in a forthcoming Resolution Foundation report.

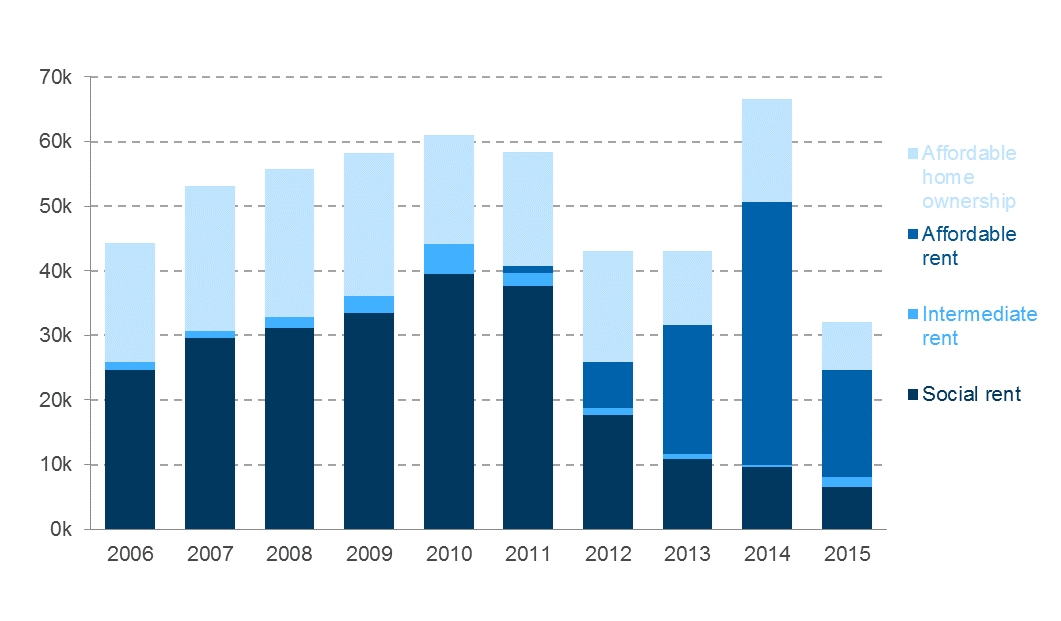

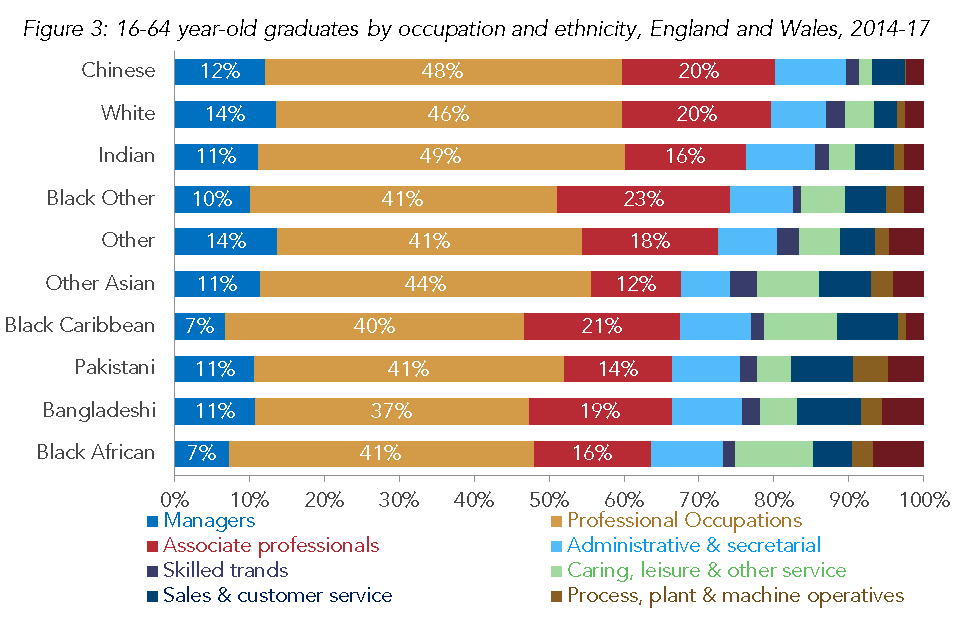

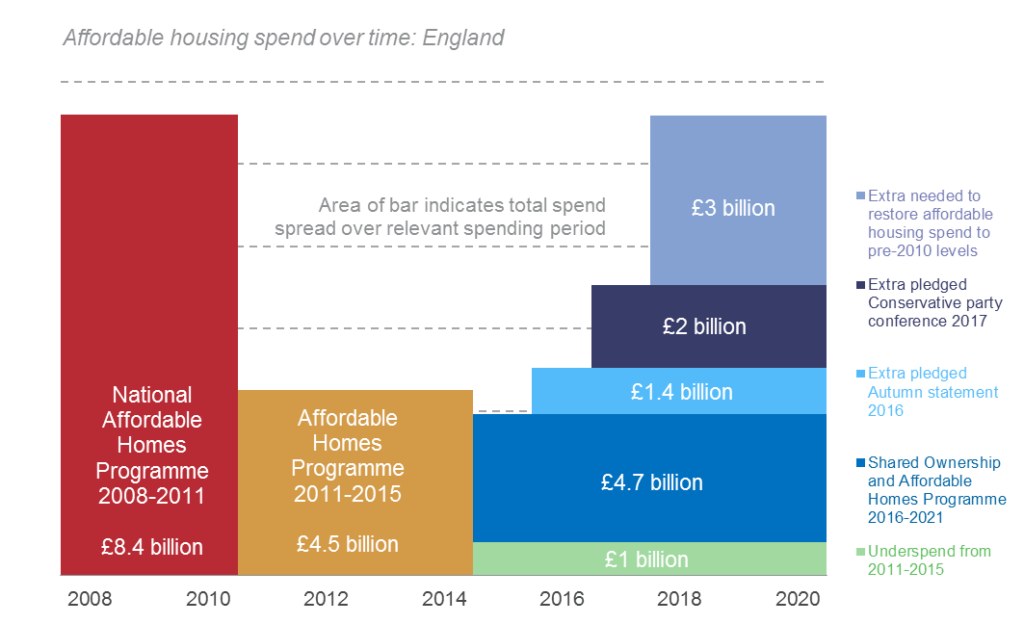

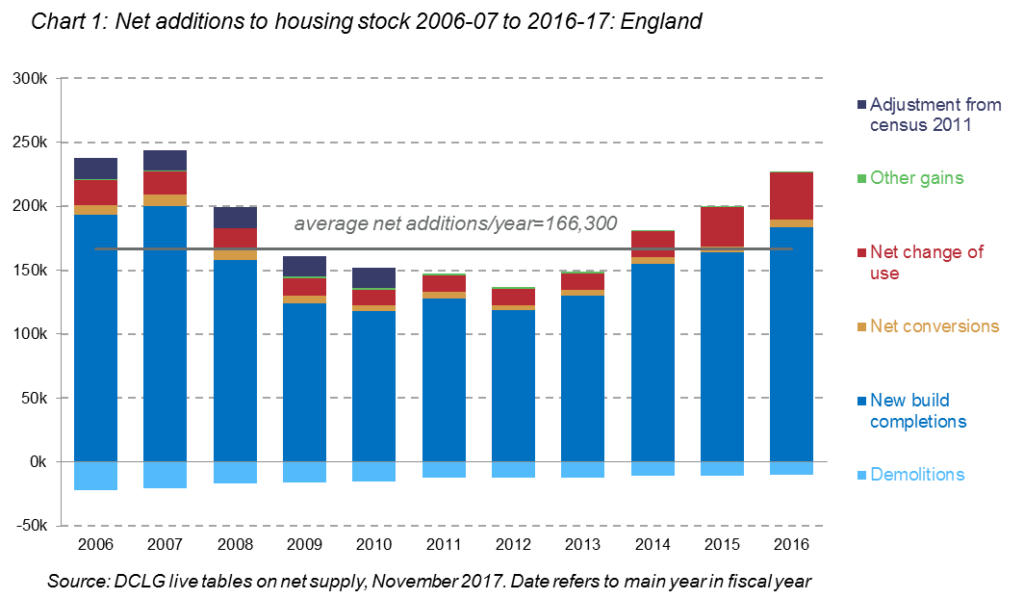

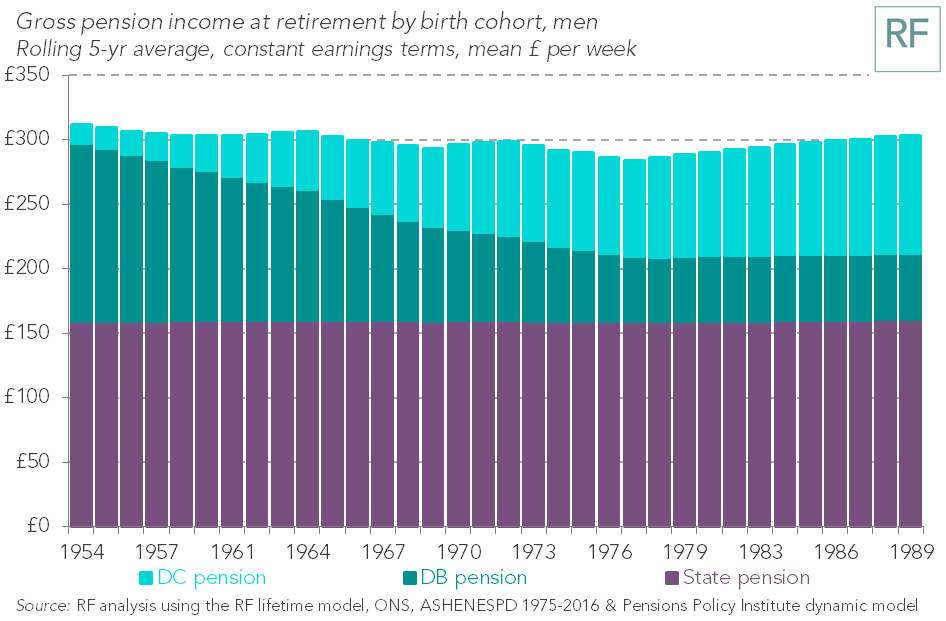

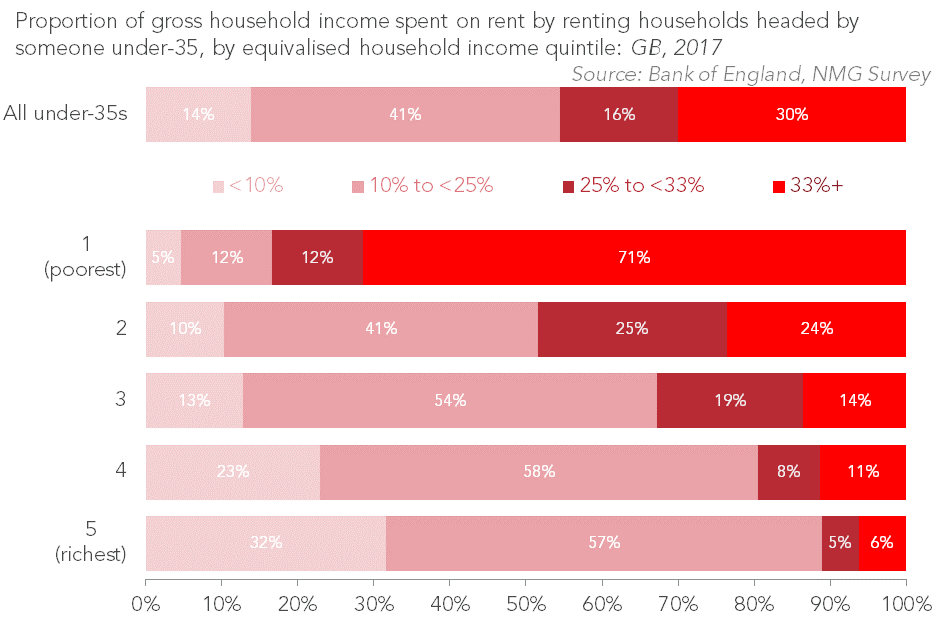

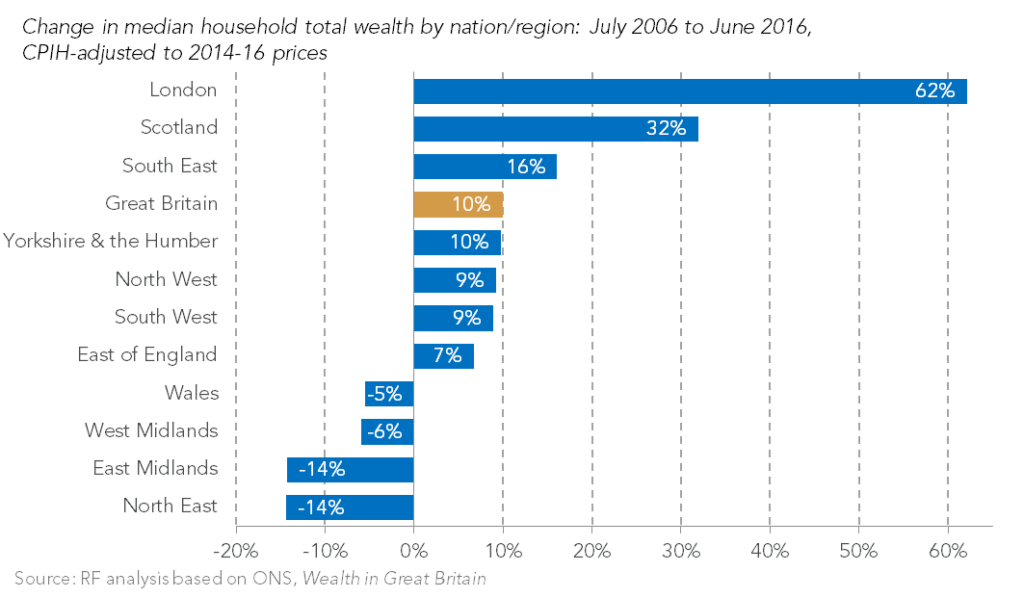

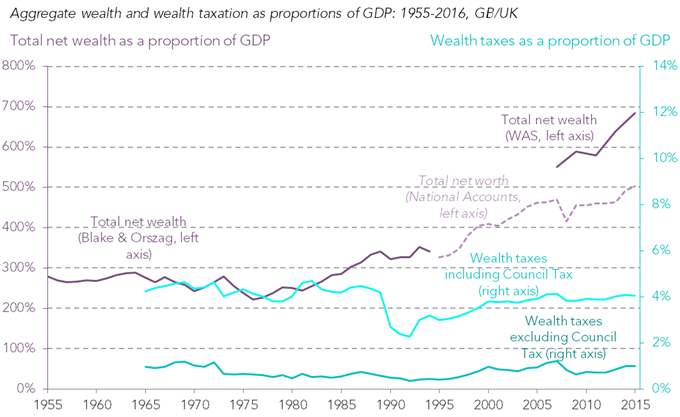

While the employment rate is a good headline indicator of labour market outcomes, it is of course important to understand the types of occupations that those graduates in work are engaged in. The ONS Standard Occupational Classification system separates occupations into 9 different categories, with those in categories 1-3 (managerial, professional and associate professional) typically classified as higher-skilled, and often ‘graduate level’ occupations. Again, when viewing occupational categories through the lens of ethnicity, there are worrying gaps. As shown in Figure 3, roughly 80% of employed white and Chinese working age graduates are in high-skilled, and on average higher paid, jobs as compared to roughly 65% of people with Bangladeshi and Black African backgrounds. Put another way, despite having achieved a degree, nearly 30% of Black African and Bangladeshi graduates work in lower skilled (lower paid) jobs.

![]()

Source: Labour Force Survey. Currently enrolled students are excluded.

![]()

Source: Labour Force Survey

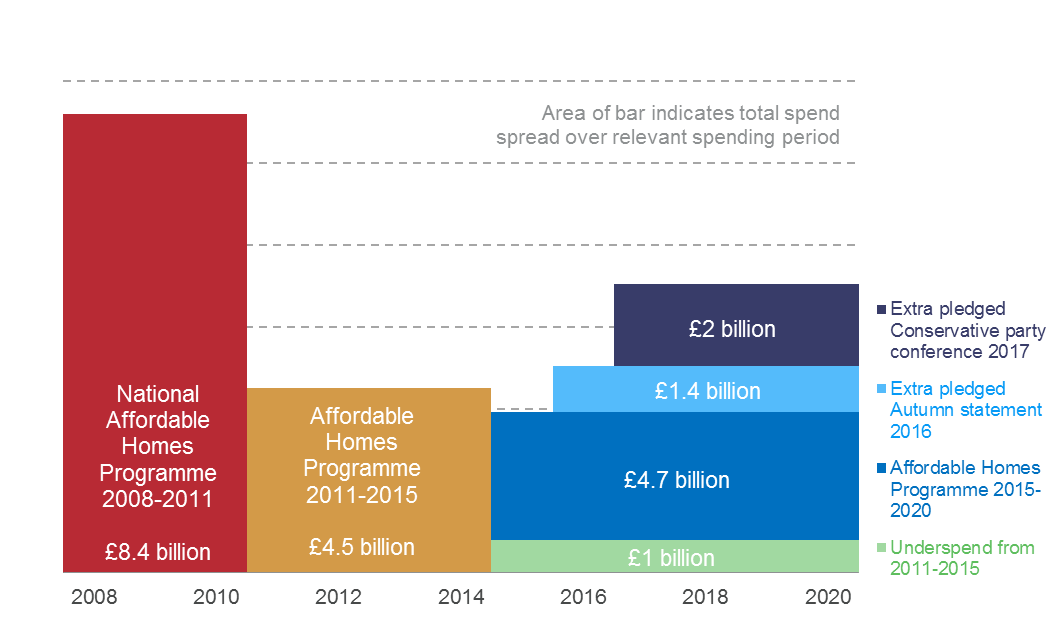

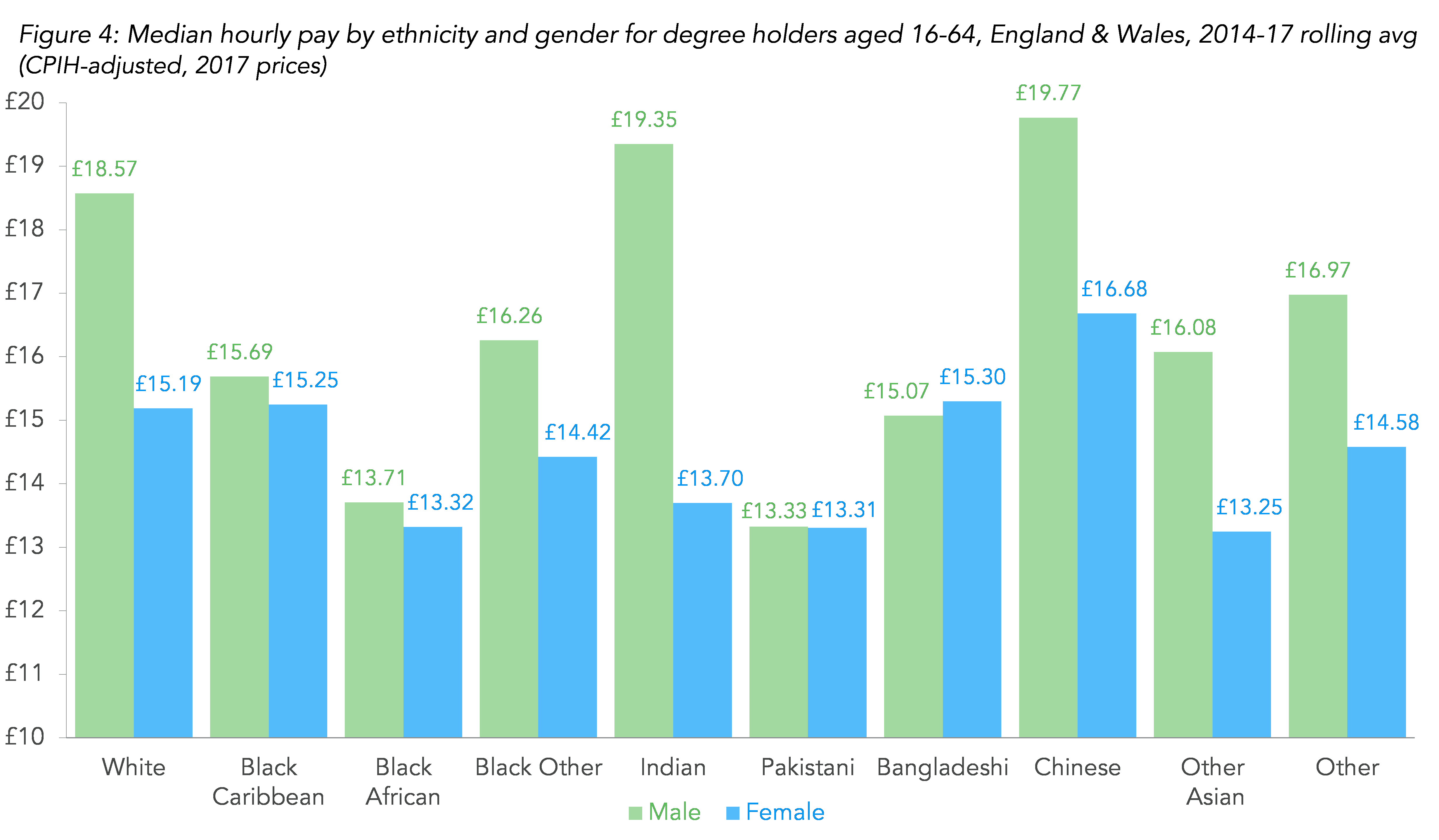

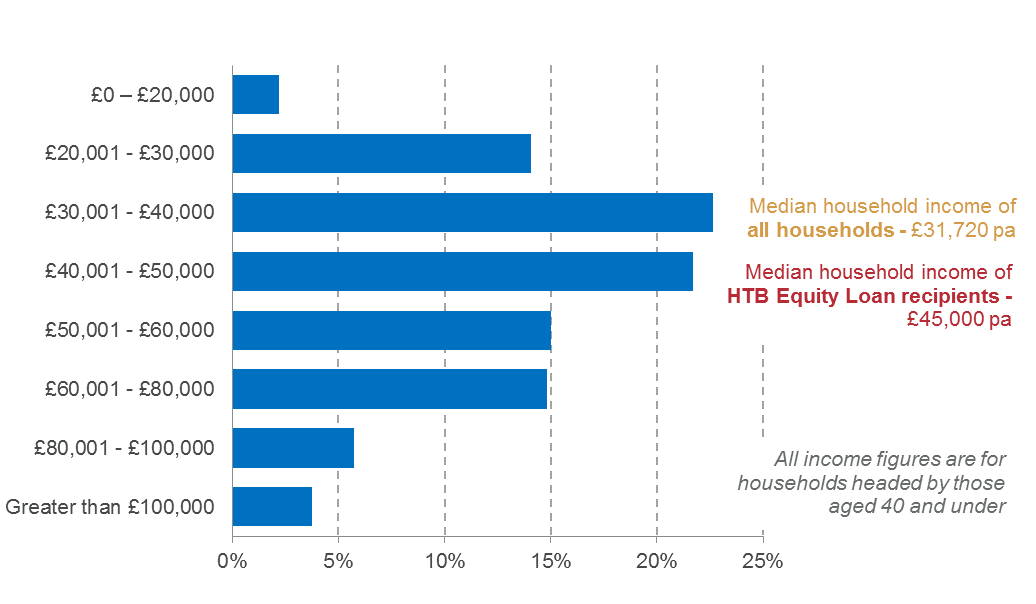

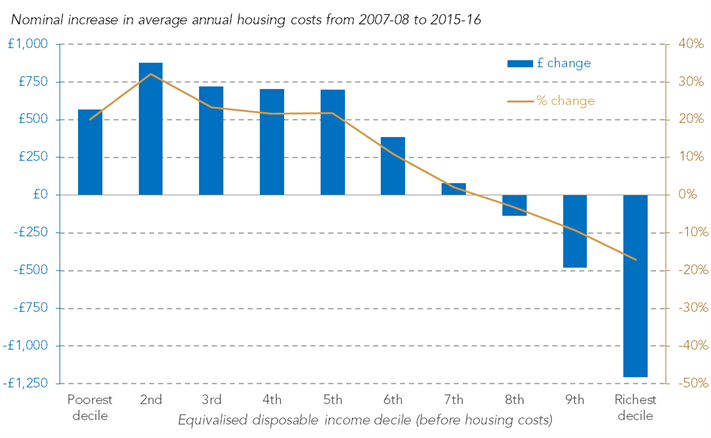

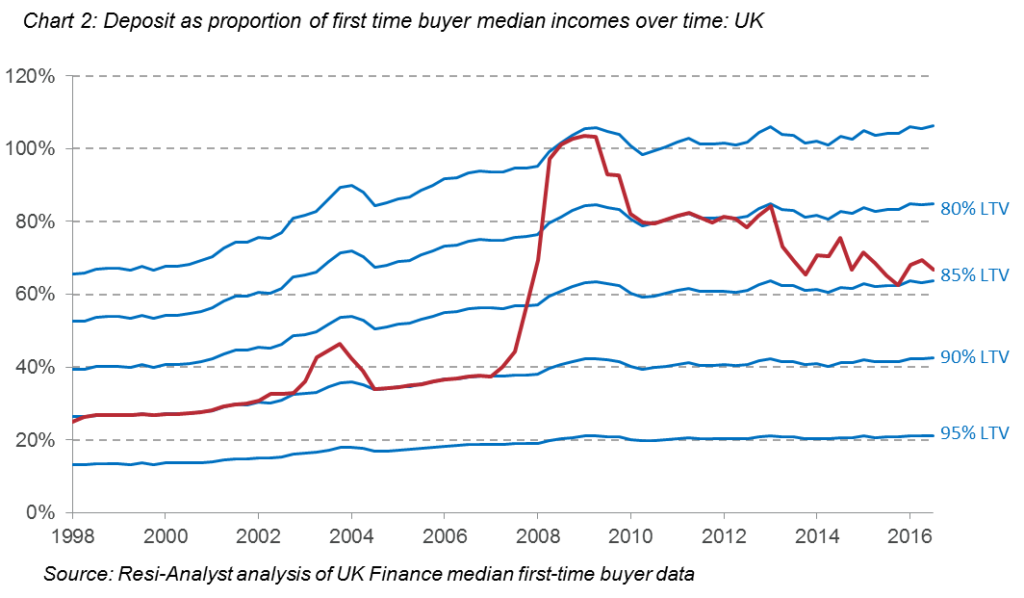

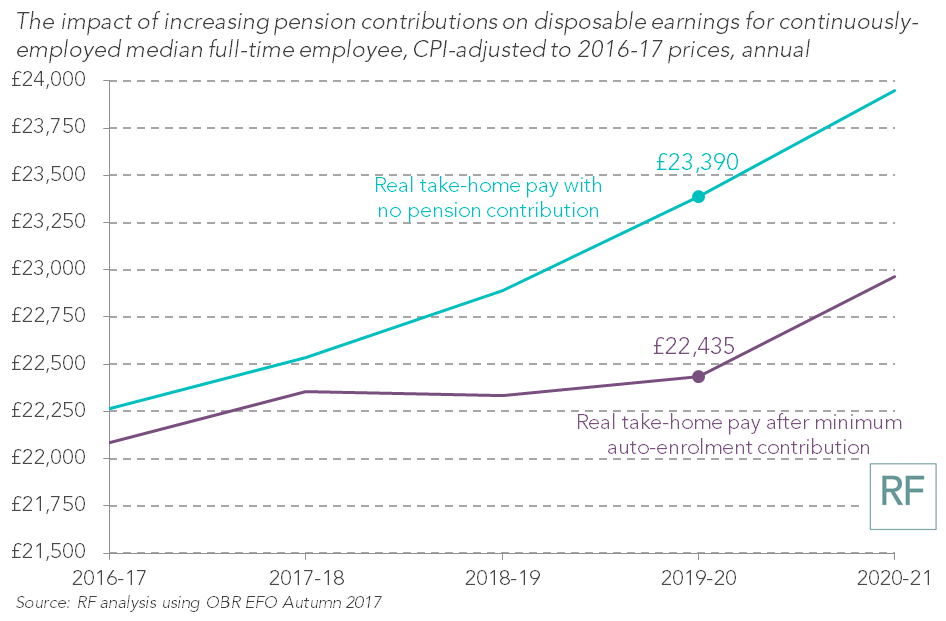

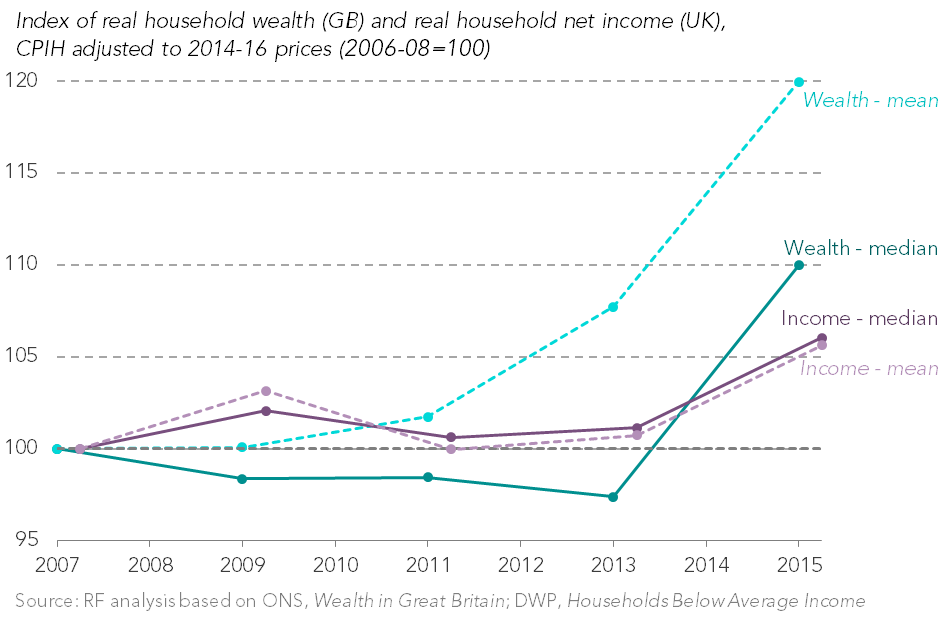

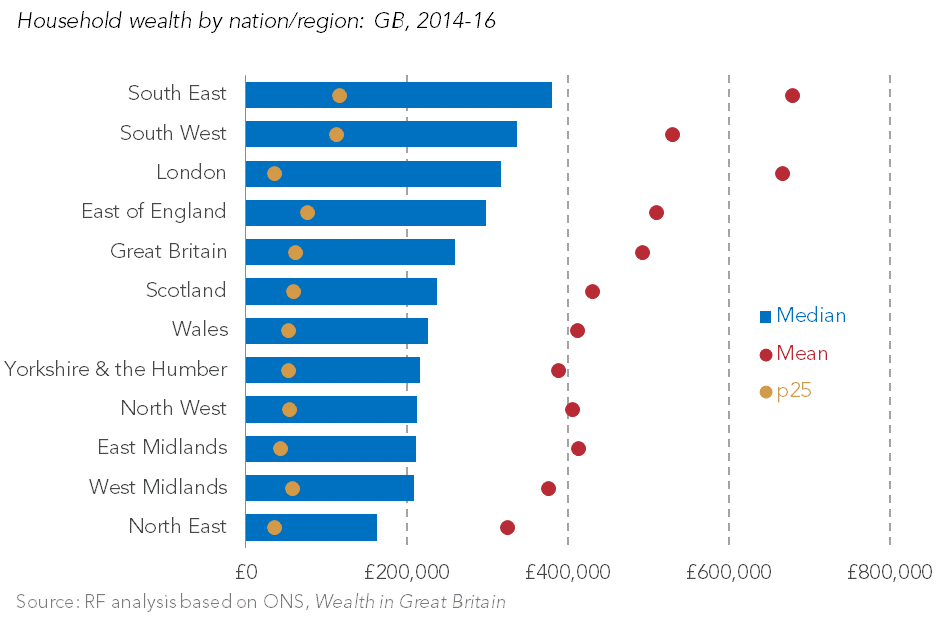

When looking at the pay landscape for different ethnic groups the picture becomes yet more concerning. Figure 4 compares the median average hourly pay for degree holders of all ethnicity categories (available in the LFS data), and includes the gender breakdown within these groups. Whilst Chinese and Indian male degree holders on average are the highest earners at £19.77 and £19.35 respectively, closely followed by white male degree holders with median hourly pay of £18.57, there is a large pay penalty for all other groups by comparison. Almost all women graduates are paid significantly less than their male counterparts, with the exception of Bangladeshi women.

![]()

Source: Labour Force Survey

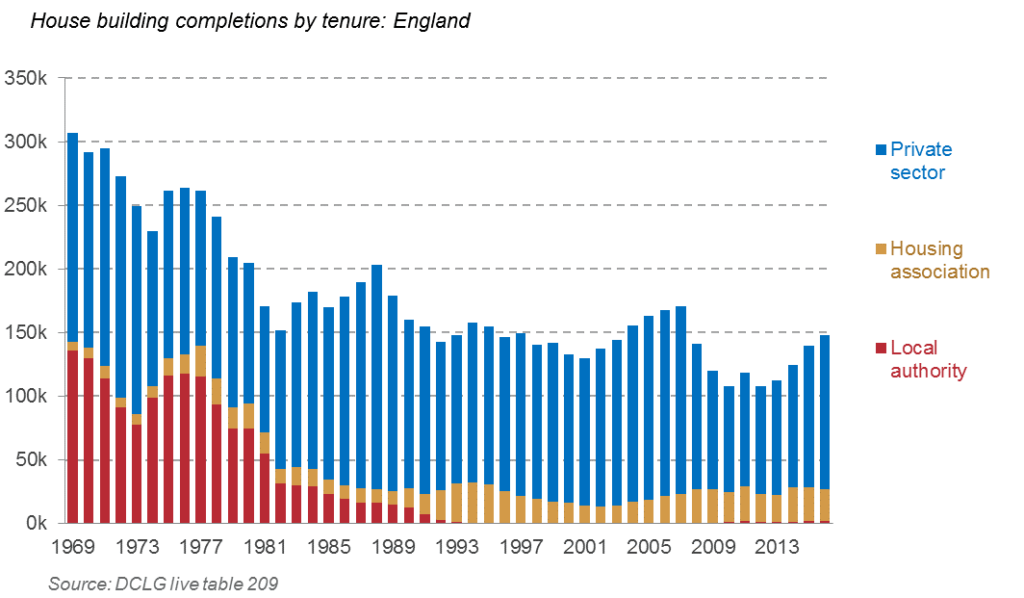

Figure 5 highlights these disparities in terms of the percentage pay gap between white male degree holders and all other ethnicities by gender. As Figure 5 demonstrates almost all groupings appear to have a significant pay penalty in comparison to the white male degree holder population (chosen as the control group as white is still the largest ethnicity in the population, and males have long been established to earn more on average than females), with the exception of Chinese and Indian males.

The largest graduate pay gap is recorded for other Asian women, followed by Pakistani men and women, Black African men and women, then Indian women who all, on average, have a recorded pay gap of nearly 30% less than white male graduates over the last 3 years. Graduate females of all other ethnicities (including the white female population) and Bangladeshi males with degrees also experience a notable pay gap of nearly 20% compared to white male degree holders. This is a concerning finding given that gaining a degree is typically thought of as being a route out of poverty and an opportunity for one to elevate their living standards and earning potential.

Whilst the findings from this most recent analysis are somewhat concerning, it should be noted that this is just a preview of ongoing Resolution Foundation research. These descriptive statistics are a powerful tool for understanding the link between attainment and employment outcomes, and how this varies for different groups and changes over time, yet they currently do not account for variation by factors including gender (in some analysis), age, region, degree subject or birth cohort. For example, compositional factors such as age may affect some of the employment and pay gaps we’ve highlighted. Further, our initial research suggests these factors will play a key role in understanding the challenges faced by Black and Minority Ethnic groups, and by looking at birth cohorts in our in-depth analysis we hope to be able to draw further conclusions into how the gaps have evolved, and whether they have reduced for younger, more diverse cohorts.

What these finding do certainly highlight is the need for a thorough investigation into the challenges faced by Black and Minority Ethnic groups in Britain today. For this reason the Resolution Foundation welcomes the Government’s Race Disparity Audit as a positive step forward in correcting these labour market imbalances, and we hope that by illuminating some of the issued faced by Black and Minority Ethnic people in the UK, policy objectives can start to be formed in response to these challenges.

The post Black and ethnic minority workers needs a bigger living standards reward for their astounding progress in getting degrees appeared first on Resolution Foundation.